Much has been said and written about the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the Indian economy, the stimulus packages announced by the Government of India and the sad plight of the migrant workers. This article brings into focus segments of the economy that constitute the bottom of the labour hierarchy, namely microenterprises, construction workers, street vendors and domestic workers. Will the relief measure help refigure their livelihoods after the lockdown is lifted?

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates informal employment worldwide to consist of 2 billion workers, or 62% of all workers. Informal employment constitutes 90% of workers in low-income countries, 67% in middle-income and 18% in high-income countries. Further, women tend to be more exposed to informality in low- and lower-middle-income countries, which makes them more vulnerable to economic shocks (ILO 2020).

The ILO estimates that worldwide, eight out of every 10 enterprises operate informally. These are mainly unregistered small-scale units, employing a total of less than 10 workers, of whom many workers are undeclared with low skills. This includes unpaid family workers, who are mainly women. The workers receive no social protection and have poor safety conditions at the workplace. These enterprises operate at very low productivity and have low rates of savings and investment, leading to negligible capital accumulation (ILO 2020).

The precarious conditions under which both the informal workers and informal enterprises operate leave them exposed and vulnerable to economic shocks. COVID-19 and the lockdown that followed was an unexpected shock. The global nature and scale of the shock left economies staggering, with the growth rate of national income plummeting to negative values.

Segments of the Informal Economy

The informal economy consists of approximately 411 million workers, estimated using the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), 2017–18 of the National Statistical Office (NSO) (Himanshu 2019). How large are the segments of informal workers and enterprises of interest to us?

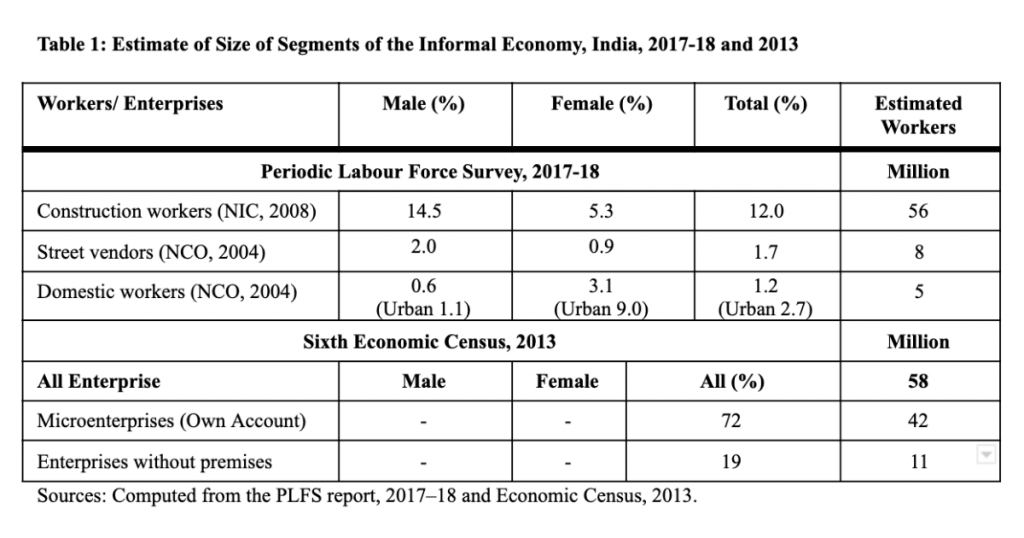

Informal Workers: The construction sector engages the second-largest component of informal workers, after the agricultural sector. It entire constituted about 56 million workers,[1] about 14.5% of male and 5.3% of female workers in 2017–18 (Table 1). This may be an overestimate of the construction labour as it includes all workers in the construction industry, including the professionals.

About 2% of all workers were street vendors,[2] a conservative estimate constituting about 8 million in 2017–18 (Table 1). Nearly 3% of women workers and 0.6% of men were engaged in domestic work in 2017–18.[3] The proportion of women workers in domestic services in urban areas was larger at nearly 95 in 2017–18. We estimate that 5 million of all workers were domestic workers in 2017–18 (Table 1). According to Dey (2020) in 2011–12, nearly 4 million workers were employed as domestic workers by private households. Both street vendors and domestic workers constitute a sizeable number of workers.

Informal Enterprise: The Economic Census, 2013 estimated that there were 58 million enterprises in India. Of these, 72% were own account enterprises that did not hire workers on a regular basis and operated with their own family labour. These constitute microenterprises and comprise 42 million enterprises. Of the total enterprises, Economic Census, 2013 estimated that nearly 19% were operated from household premises, constituting 11 million enterprises. The small scale of operation of such microenterprises makes them particularly vulnerable to an economic shock such as the lockdown.

Relief Measures and Impact on Selected Segment of Informal Economy

Microenterprises: The sudden lockdown leading to stoppage of economic activity and restriction of movement of people and goods had a tremendous impact on microenterprises. The government announced a Rs 20,000 lakh crore relief package in five tranches. In the relief packages announced by the Government of India, many measures were declared for the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME). A few of them are listed below:

- Credit Guarantee Scheme, collateral-free credit: Additional Rs 3 lakh crore without fresh collateral to MSME and Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency (MUDRA) borrowers, expected to benefit 45 lakh units.

- Interest rate cap of 9.25% for banks and financial institutions and 14% for non-banking financial companies (NBFCs).

- Micro-food and fisheries: Credit-linked subsidy to 2 lakh micro enterprises (interest concession). In micro-food enterprises: Rs 10,000 crore, fisheries Rs 20,000 crore.

- Avail new equity from Rs 50,000 crore fund.

- Definition of an MSME is being expanded to allow for higher investment limits and the introduction of turnover-based criteria.

- 24% of monthly wages to be credited into provident fund accounts for the next three months for wage earners below Rs 15,000 per month in businesses with less than 100 workers.

In the first tranche of relief, a credit guarantee scheme for MSME was announced to the tune of Rs 3 lakh crore. The total outstanding to MSME was pegged at nearly 5 lakh crore and the finance minister announced that the central government and public sector undertaking (PSU) would clear the pending dues within 45 days (Magazine and Suri 2020). However, a large part of these dues are also from the larger private companies. The government did not seem to have the wherewithal to compel these private companies to pay back the MSMEs. In times of high economic growth, these dues may matter less as cash flow would exist. In times of economic shock, these dues, if paid, would help sustain them for a while and pay their workers.

Concerns: This loan relief measure stated that these loans are available to companies with outstanding loans up to Rs 25 crore and an annual turnover of Rs 100 crore. However, the cabinet approval later “clarified” that the loan was for dues pending for up to 60 days prior to 29 February 2020. This is shocking as it means that there is zero relief for companies hit by two months of lockdown (Sridhar 2020).

Regarding the efficacy of loans in times of the pandemic, Raghuram Rajan (2020) stated “Loans take time to work. Hunger is an immediate problem. MSME are much indebted, loans add to it. Banks may use the credit guarantee to bail themselves out and not to lend.”

Sridhar (2020) has described the plight of the small enterprises that had been engaged in sub-contracted or job work for larger enterprises. With the sudden lockdown, the production chains were broken, leaving these small enterprises in the lurch. He documents cases where entrepreneurs of such enterprises had to take a loan to make goods and services tax (GST) payments. Invoices to large enterprises for supplies made have not been paid, but the micro and small enterprises are responsible for paying the tax that needs to be collected from the client. Could the government give some concession or extension for GST payment till the economy is on its feet again?

Under the Atmanirbhar Bharat package, the centre has announced a credit-linked subsidy to microenterprises in food and fisheries to the tune of Rs 30,000 crore. But 40% share of these funds is supposed to come from the state governments. In this crisis situation, do the states have funds to finance this scheme?

In times of this economic shock, the MSMEs are struggling to pay the workers for the months when they worked and during the lockdown. It is not surprising that most of the migrant labour working in these units is heading home. The labour ministry notified a special scheme wherein the government will contribute 24% of the employee and employer’s share of provident fund per month for three months for employees earning less than Rs 15,000 (Economic Times 2020). If implemented, this will be a great help to microenterprises hit by the lockdown.

Change in definition of MSME: A disturbing feature is the announcement to expand the definition of MSME to allow higher investment limits. One of the concerns with the schemes of the Ministry of MSME has been that it caters to all sizes of enterprises. The result is that the microenterprises find it difficult to access schemes, while the medium-sized enterprises with greater resources are able to get the benefit. In this context, if the upper limit of the definition of MSME is raised, it will further tilt the balance of resources in favour of larger enterprises. The idea apparently is to allow the enterprise at the upper limit of the definition to grow and yet obtain the benefits of the scheme. However, what was the need to do this now when all enterprises and particularly the micro enterprises are stressed?

The change in definition of MSME also includes an increase in turnover limits to 100 crore, likely to be raised to 200 crore as suggested by the industry. “There are several industries where the investment in machinery may not be high, but because of expensive raw material, their turnover increases,” according to Anil Bhardwaj, secretary general at Federation of Indian MSMEs (FISME) (Saluja 2020).

Recommendations for refiguring livelihoods among microenterprises: There is likely to be an uneven impact of the crisis on different sectors of the MSME, and this may trigger large-scale restructuring of economic activities. It would be helpful if the ministry could work out a road map of reallocation of informal (formal) labour towards less severely affected sectors or sectors where consumption demand might recover. This is, of course, easier said than done, as the skill sets required may be quite different in the various industries.

Other measures are to reduce operating costs, waivers or deferred payments for public services, such as electricity, water or rent, will greatly help the microenterprises. Further, subsidies in the form of reduced rates for mobile calls and internet access and training may enable microunits to experiment with digital tools for business continuity and income generation (ILO 2020).

Construction workers

In the run up to the implementation of the GST in July 2016, the central government quietly repealed several acts that provided for welfare of informal workers in many unorganised sectors (Unni 2018). In April 2017, the Taxation Laws (Amendment) Bill abolished welfare cess levied to many industries, including the beedi workers welfare cess, along with the duty of excise (KPMG 2017). Some relief measures announced for the construction sector are:

- Direct benefit transfer to registered workers under BoCW using cess funds.

- Construction, goods and services: Government contracts stalled due to COVID-19 will be given a six-month extension for completion.

- Partial bank guarantees to be released by the government for part of the construction completed.

As per an advisory from the centre, 18 states transferred Rs 1,000–5,000 to bank accounts of registered construction workers hit by the COVID-19 pandemic from the designated cess funds under the BoCW Act. States disbursed a total of Rs 2,250 crore as one-time cash benefit, directly into the accounts of around 18 million construction workers in distress. According to trade union sources, the transfer per registered worker in different states was as follows: Rs 5,000 in Delhi, Rs 3,000 in Punjab and Kerala, Rs 2,000 in Himachal Pradesh, and Rs 1,500 in Odisha (Ray 2020).

The extension of time for completion of contract for construction and the partial bank guarantee for the completed part will help the industry revive when the economic activity begins.

Concern regarding non-registration of construction workers: On 30 September 2018, India had 32 million construction workers registered with the BoCW, distributed in Uttar Pradesh (42 lakh), West Bengal (31 lakh), Madhya Pradesh (30 lakh), Tamil Nadu (29 lakh), Odisha (22.5 lakh) and other states (Ray 2020). The PLFS, 2017–18 estimated 56 million construction workers. This leaves a gap of 26 million construction workers who were not registered under the BoCW Act and therefore will not receive the direct benefit transfer. These construction workers who were unregistered for no fault of their own, will not receive even this small one-time benefit in this period of dire crisis.

The government announced that Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) will get an additional Rs 40,000 crore. Further, wages under MNREGA will also be increased by Rs 2,000 per worker as additional income to help daily wage labourers. These are welcome steps for construction workers and other migrants who have lost jobs and have returned home due to the lockdown.

Street Vendors

Street vendors and other informal workers, other than migrant workers, have hardly found mention in the relief packages. Street vendors are better off in this regard, partly because they are a visible and integral part of the trade sector of the country. Some relief measures that directly or indirectly helped the street vendors were:

- Special liquidity scheme to provide Rs 10,000 working capital to 50 lakh street vendors.

- Street Food Vendors: Below poverty line (BPL) families will get free cylinders for three months under the Ujjwala scheme.

- 20 crore Jan Dhan women account holders will receive compensation of Rs 500 per month for the next three months. This is applicable to all women with accounts.

Concerns: In the context of lockdown, we can distinguish three categories of street vendors

Group 1: Trade in “essential” commodities: vegetables and fruits

Group 2: Trade in “semi-essential” commodities: street food

Group 3: Trade in “non-essential” commodities; cloth, plastics

Vendors in group 1, that is those who trade in essential commodities, such as vegetables and fruits, can operate if they have their vendor licence and additionally may require a health permit. All normal barriers to entry may apply here as well. Group 2 includes trade in “semi essential” commodities, such as street vending in food, and it is under the scanner due to reasons of health and hygiene. However, this is also an essential commodity as many persons living or stuck outside their home towns and cities need a source of cooked food. Their situation is precarious and likely to remain so even after the lockdown is lifted as concerns of hygiene, permits under the Food Safety and Standards Act, social distancing, and decline in demand will hit them. In group 3, vendors of non-essential commodities, such as cloth, plastics, etc, are in the most precarious situation as both their demand and supply are compromised. Demand is hit due to lack of money in circulation, and supply has been impacted due to closure of units producing these commodities.

Arbind Singh, national coordinator of the National Alliance of Street Vendors of India (NASVI) felt that benefits of loans were unlikely to provide relief. “With cash flows drying up, hundreds of street vendors have already used working capital for their day-to-day expenses and are now left with no money in hand, measures such as direct cash transfer is the need of the hour” (Sen 2020). Ghosh from the National Hawker Federation recommended seeking interest-free loans and provision of MUDRA loans with subsidies. Ghosh also demanded that state committees with representatives from vendors’ associations should be formed. The “legally mandated street vendor survey has not been done and only 10 percent of the total vendors have been surveyed” (Sen 2020).

Domestic Workers

Domestic workers are the most invisible and consequently vulnerable group among the informal workers. They are faceless and voiceless. This was clear as there was no space for them in the relief measures. The vulnerability of domestic workers was seen in the fact that the employers and resident associations/housing societies would not let them in, seeing them as a health risk.

The associations of domestic workers made efforts to voice their claims. Bharati from Rajasthan Mahila Kaamgar Union said, “Government should put a mechanism in place, ensure that domestic workers get a basic salary.” Velankar from Jagori, Delhi demanded that “Government should have dialogue with Resident Welfare Association (RWA) to ensure that these workers get paid by employers, who are members of RWA, for the lockdown period.” While most state governments were silent, Menon from the Domestic Workers Rights Union noted that the “Karnataka Chief Minister gave statements that employers should not fire their domestic workers. But because there is no rule or written order in place, there are many who are not complying to this” (Dey 2020).

Many domestic workers had suffered a pay cut in March and received no pay in April. A survey of 80 domestic workers from Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Maharashtra and Gujarat was conducted by the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad between 24 April and 1 May 2020. Though interviews were conducted in the middle of the lockdown, 25% of the women were continuing to work. The mean and median salary in the last month before the lockdown, February, was around Rs 4,000–5,000. In March, 24% of the respondents received no salary at all and 44% received a salary cut even though they had worked for most of the month. The positive aspect was that 13 respondents (16%) reported getting an advance for their April salary ranging from Rs 500 to Rs 8,000. On average, the advance was close to Rs 4,000. This meant that in the absence of social security cover and access to credit, the domestic workers were dependent on their employers making them more vulnerable.

Other problems faced by domestic workers and other informal workers were not having enough ration, with only few workers receiving free ration and direct benefit transfers from the government. Many of these workers faced domestic violence while being confined at home, unable to contribute to household resources.

The livelihoods of the domestic workers may be at risk even after the pandemic passes as the employers may not hire them back. If they consider shifting to related occupations, they would require support for skill training and provision of loans.

Conclusions

The future remains unknown for most informal workers and enterprises. So far, the government was only anticipating a slowdown in growth of the economy due to the pandemic. However, the first admission of a recession was when the Reserve Bank of India announced on 22 May 2020 that the country is going into negative growth. As economic activity is not likely to revive soon, the demands of the trade unions seem very relevant. The Central Trade Unions demanded that the workers be assured wages for the entire lockdown period and direct cash transfer of Rs 7,500 to non-income tax paying households, including unorganised labour force, for at least three months. The situation is indeed frightening.

Source: EPW – engage